- Home

- Thomas E. Sniegoski

A Hundred Words for Hate rc-4 Page 3

A Hundred Words for Hate rc-4 Read online

Page 3

“Bad piece of fish?” Remy echoed. “I look that bad?”

Mulvehill nodded. “Something isn’t sitting right with you.”

The bartender brought them two fresh drinks, and was off to the other end of the bar in a flash.

“It’s stupid,” Remy said. He drained what remained of his first drink and set it down before picking up the second.

“Figured as much,” Mulvehill said. “Why don’t you share the stupidity so I can get a good laugh.”

“It’s because I had a good time,” Remy mumbled, embarrassed as he heard himself speak the words.

“You look like you’re smelling low tide at Revere Beach because you had a good time? What’s wrong with this picture?” And then Mulvehill’s expression changed. “This is about Madeline, isn’t it?”

Remy said nothing.

“Jesus, Remy,” the homicide cop said. “Can’t you cut yourself the tiniest bit of slack?”

Remy knew that Steven was right, but it didn’t change how he felt. “I know it’s crazy,” he admitted, “but I can’t shake the feeling that . . .” He stopped, staring at the ice in the bottom of his glass.

“That you’re cheating on her,” Mulvehill finished the sentence for him, his voice low and rough.

Remy nodded once. “Yeah, something like that.”

“You know that’s not true, right?”

“Yeah.” Remy nodded again.

“This isn’t helping you at all, is it?” Mulvehill said.

Remy started to laugh. “Not at all.”

Steven laughed too, picking up his drink and taking a large swig. “You’re your own worst enemy, Remy Chandler,” the homicide cop said.

“Ain’t it the truth,” Remy had to agree.

They were quiet again, the sounds of the bar swirling around them as they sat and drank. There was a tickling at the base of Remy’s brain, and suddenly he could hear a voice—a prayer—ever so softly from someone in the bar. The person was praying for his mother, who was dying. He was praying that her life would end soon.

That there would be an end to her suffering.

“So where’d you leave it?” Steven asked, the distraction an answer to Remy’s own silent prayers.

“We’re supposed to have lunch tomorrow.”

“So you’re going to see her again?”

“Yeah,” Remy said.

“Good. You shouldn’t be alone.”

“You’re alone,” Remy countered, turning to look at Steven.

“But, you see, that’s the difference between us,” the cop explained. “I’m better off alone because I’m a miserable bastard, but you . . . Let’s just say you need a good woman to keep you in check, and we’ll leave it at that.”

Steven was right.

Since the death of his wife, Remy was finding it more and more difficult to control the angelic nature that writhed and churned inside him—desperate to be released, desperate to do what he was created for.

The Seraphim was a soldier—a warrior of God—and he existed to burn away anything that was a blight in the eyes of God. A power such as that had to be controlled.

Steven knew that, and knew that it was the love of Madeline that had kept the destructive, divine power in check for all these years, a love that had kept Remy anchored to the mask of humanity he’d created for himself as he lived upon the world of God’s man.

An anchor that was now missing.

“What makes you think Linda will be able to fill that role?” Remy asked him.

Steven shrugged. “I don’t, but at least you’re out there trying . . . acting like all the other poor schmucks looking for love.”

“Except you,” Remy said.

“I eat love for breakfast and it gives me the wind something awful,” Mulvehill said with a snarl as he finished what was left of his drink. “I need a cigarette and my bed, in that order.”

He fished his wallet out from the back pocket of his pants as he slid from the stool. “I got this,” he said, pulling out some wrinkled bills and placing them on the bar. He gestured to the barkeep and took his coat from the back of his chair.

“Wow, even after I pissed you off you’re still picking up the tab,” Remy said, slipping into his own leather jacket.

“What can I say,” Mulvehill said, pulling a crumpled pack of cigarettes from an inside coat pocket. “I’m generous to a fault.”

Remy followed his friend outside into the freezing cold. The smokers who had been there when he’d first arrived were long gone.

“Shit, it’s cold,” Mulvehill said as he yanked the collar of his coat up around his ears. A cigarette protruded from his lips, and he brought a lighter up to ignite its tip.

“It’s January in New England; what do you expect?” Remy commented.

“Thank you, Al fucking Roker,” Mulvehill said dryly, making Remy laugh. “Where’d you park?”

Remy pointed to his Toyota across the street. “There she be,” he said. “Where are you?”

“I walked; figured it’d be one of those exasperating nights where I needed many drinks to keep from strangling you.”

“And was it?” Remy asked.

“You were one Scotch away from being throttled,” his friend said, cigarette bobbing between his lips.

“Guess it’s my lucky night,” Remy said. “Want a ride?”

Mulvehill shook his head. “Naw, gonna walk off the buzz.” He started to back up down the street.

“Talk to you later, then,” Remy said, walking into the center of the street. There wasn’t a trace of traffic as he strolled to his car.

“Hey, Chandler,” Steven called out as Remy stuck his key in the door of his car.

“Yeah,” he answered.

“Can’t imagine she wouldn’t want you to be happy,” his friend said.

“You’re probably right,” Remy answered, letting the words slowly penetrate, knowing full well whom Steven was talking about. Pulling open the car door, he waved good night before climbing inside.

Can’t imagine.

Odd jobs—that was all he could remember doing for . . .

It seemed like forever.

They called him Bob, but he had no idea where the moniker had come from. He couldn’t remember his real name.

He couldn’t remember much of anything.

Bob was waiting in front of the Home Depot with ten others, waiting for work. They would do just about any form of manual labor for a day’s pay—gardening, painting, yard cleanup . . . odd jobs.

Odd jobs.

Bob stood by himself, away from the others, as he usually did, eyeing the entrance to the parking lot.

The smell was upon him first, a wave of hot, fetid aromas—the stink of a primordial jungle, lush with thick, overgrowing life. Bob closed his eyes, suddenly feeling as though he’d moved through time and space to another location.

A place that he could almost see inside his mind. A place where he had been before.

This wasn’t the first time he’d experienced this, but it was stronger of late, the smells more specific, the imagery more precise, and he kept hoping that one day soon, he would remember more.

More than the odd jobs.

“Hey, you comin’?” a voice asked, interrupting his thoughts.

Bob opened his eyes to see a thin Hispanic man standing in front of him. The others were already climbing into the back of a silver pickup truck.

“Yes,” Bob answered quickly, the lingering scent of the forest fading from his nostrils as he joined the other day laborers.

After a short drive, they ended up in a well-to-do neighborhood, clearing an overgrown lot to make way for the renovation of an existing property. Bob knew little more than that, and really didn’t care.

He couldn’t forget the latest assault to his senses. It was right there, teasing him, telling him something he needed to know, but didn’t understand.

Almost as if the memory were in some foreign tongue.

Bob stood in the lot, a scy

the in his hand, cutting a swath through a thick wall of overgrown weeds. He concentrated on the rhythmic, back-and-forth movement of the blade, trying to forget the smells, the sensations, but elusive echoes remained, just beyond his reach.

The morning sun climbed high in the sky, and his shirt was soaked with the perspiration of hard work. Heart hammering in his chest, Bob let the scythe drop and removed his shirt, exposing his well-muscled flesh to the sun’s rays.

The high-pitched sound of a child’s laugh caught his attention and he gazed back toward the well-kept yard beyond the lot. The man who owned the property—Bob didn’t remember if he had even told them his name—was spraying a gleefully shrieking little boy with a garden hose.

Bob’s eyes were riveted to the scene, locked on the image of the happy child racing around the yard, trying to avoid his father’s attempts to soak him. It was all so . . . familiar.

And suddenly, the laughing child was replaced by the image of a man and a woman . . . naked, perfect in their form. They too ran through a gently falling rain.

A rain that fell upon a garden.

The Garden.

Bob let out a scream of agony and fell to the dusty ground he’d just cleared. For years—centuries—he had waited for a time when his visions would reveal their secrets, but now he wanted them to stop.

His fellow workers crowded around him.

“Is he okay?” the home owner called out. “Should I call nine-one-one?”

The silence in Bob’s mind was nearly deafening now, and he felt that the world had stopped for him—waiting to see what was to come.

Waiting for him to remember.

The man still had the hose in his hand, a steady stream of water arcing through the air to drench the grass.

The child stood watching, wet and shivering.

Why does he shiver? Bob wondered. Does he sense what I do? Does he know it’s coming?

Something was returning after so very long away.

It was almost here . . . but what was it? The images pounded furiously in Bob’s skull, and he screamed as the visions exploded in front of him.

If only the others could see, they would be screaming as well.

He saw the Garden, in all its wondrous glory, and in its center was the Tree . . . the Tree pregnant with fruit.

Forbidden fruit.

Bob was standing before the Tree, gazing at the pendulous growths that hung from its verdant branches, and somehow he knew that a piece of fruit was missing.

The sword of fire that he clutched in his armored hand blazed all the brighter . . . hotter . . . fiercer. And he was incredibly sad, for he knew that they must be punished.

They. Must. Be. Punished.

A hand . . . a human hand dropped down upon Bob’s bare shoulder, rousing him from his vision.

But now he knew.

He gazed into the frightened eyes of his fellow workers.

“Call nine-one-one,” the Hispanic man who had brought them here called out to the man with the hose.

“No,” Bob said, reaching out to grab hold of the man’s wrist. He could already feel his body changing. His skin was on fire . . . the flesh starting to bubble, pop, and steam.

The Hispanic man started to scream, but only briefly as his body ignited as if doused with gasoline.

And then they were all screaming . . . screaming as Bob’s flesh melted away, dripping like candle wax to the parched earth that he knelt upon. There was metal beneath the faux flesh, metal forged in the furnaces of Heaven, and it glistened unctuously in the noonday sun.

Bob rose to his feet, twice as tall. Powerful muscles on his back tensed painfully, then relaxed as a double set of mighty wings unfurled, shaking off flecks of fire that hungrily consumed the dry grass around him.

The fires of Heaven raged, the cries of his fellow workers abruptly silenced as they were returned to the dust from whence they came.

Remy and Madeline were sitting side by side in two white wicker chairs on the front porch of their cottage in Maine.

This had always been their favorite time, when the day eventually succumbed to the night. Usually they’d had their supper, and then retired with a cup of coffee, or a cocktail, to the peace of the porch and the surrender of daylight.

The nocturnal bugs were tuning up, preparing a woodland symphony just for them. At least, that was what they had liked to think: a concert of clicks, buzzes, and hums for their listening pleasure only.

“Hey,” Madeline said, reaching across to give Remy’s hand a loving squeeze.

“Hey back,” Remy said, smiling at her. It was always good to see her, even though it broke his heart every time.

“Good day?” she asked, as they gazed into the darkness beyond the porch. It sounded as if every insect in the woods had something to say . . . something to sing about.

Remy was silent, not quite sure how to answer.

“What?” Madeline asked, turning to him with the smile that transformed his insides to liquid.

“Interesting day . . . and night,” he said, not looking at her.

“Is that a touch of guilt I hear in your voice?”

Remy shrugged noncommittally, even though he knew she had the answer.

“You realize that’s a waste of perfectly good guilt,” Madeline stated, continuing to rub the side of his hand with her thumb.

“Perfectly good guilt?” he repeated with a grin, finally turning to face her with a look of feigned innocence.

“Mmmmm-hmm,” she replied with a quick nod. “All that energy could be put to good use elsewhere, like returning your phone calls, or giving to that kid outside the Market Basket collecting for Pop Warner.”

“I didn’t have any change that day,” Remy protested.

“And taking Marlowe to the Common,” Madeline continued, ignoring his outburst. “Poor baby hasn’t been to the Common in days.”

“It hasn’t been days,” Remy attempted, before realizing that she was right.

“See, perfectly good guilt going to waste over me.”

“Nothing ever went to waste over you,” he said, missing her more at that moment than he had in some time, knowing that this wasn’t real, but realizing it was better than nothing.

“Ah, flattery.” She squeezed his hand. “So, what was it like?” Madeline asked. “Being out on a date after all this time?”

“Different,” Remy said. “Nerve-racking.” He started to laugh.

“What’s there to be nervous about? You always gave good date.”

“Gave good date?” Remy repeated with a chuckle.

“It’s true,” Madeline said. “You were the best I ever dated. I always had the nicest times with you.”

“You brought out the best in me.” Remy leaned forward and kissed her hand.

“See?” Madeline said. “Even now you’re giving good date.”

“This is a date?” Remy asked.

“What would you call it?” asked the woman he had loved for more than forty years. “You’ve created this place in your head so we can spend some time together, and here we are, enjoying each other’s company. I’d call it a date.”

“Well, I’m not sure what kind of date I was the other night,” Remy said, reflecting on his dinner with Linda.

“Why, did you make her run screaming from the restaurant?”

“No.”

“She didn’t eat with her hands, did she?”

“No, she knew how to use a knife and fork.”

“Phew.” Madeline rolled her eyes. “For a minute there I thought maybe—”

“She wasn’t you,” Remy interrupted quickly, his heart filled with emotion for the woman who had made him what he was.

Who had made him human.

“Excuse me?” she asked.

“I don’t think I was very good company because I kept thinking that I’d rather be with you.”

“You’re so sweet,” Madeline said. She reached over and placed her warm hand against his cheek. “And I’m flattered,

really, but I’m also dead, Remy. The only way we can see each other is like this. Just you and me . . . and your very active imagination.”

They were both silent for a moment, listening to the insect song.

“You didn’t bring me up, did you?” Madeline asked finally.

“No,” Remy said. “I didn’t think it would be appropriate.”

“Thank God for that,” she said with a gentle laugh.

“Hey, I’m not as hopeless as you think I am,” Remy defended himself.

Madeline leaned over and put her head on his shoulder. “You’re not hopeless at all,” she told him. “Just a little bit stubborn sometimes.”

“Ya think?” Remy asked, putting his arm around her.

They sat like that for quite some time, Remy not wanting to speak—not wanting to ruin the moment. It felt like it had when everything was perfect.

When everything was just right.

“Did you have a little bit of fun?” she asked him.

“Maybe a little,” he answered, immediately feeling that twinge of guilt.

“How much?” Madeline asked, sitting up and turning to face him. She held up her thumb and forefinger about an inch a part. “This much?”

Remy shrugged. “Maybe a little less. She had a runny nose.”

Madeline wrinkled hers. “Really?”

Remy nodded. “Yeah, it was cold, though, so I guess I should cut her some slack.”

“I guess,” Madeline agreed. “Do you think you’ll see her again?”

Remy didn’t want to answer that question.

“Remy,” Madeline said, trying to get his attention.

He looked at her then, wishing with all his heart that this could be real.

“I asked you a question,” she said, her beautiful gaze urging him to answer.

“Yes,” he finally replied, and as the words left his mouth, the sounds of the forest were suddenly—eerily—quiet. “Yes, we’re having lunch tomorrow.”

Madeline smiled then, a smile that he’d seen thousands of times, a smile that had never failed to warm him to his core, a smile that personified the love she’d felt for him, reflected back as the love he had for her.

“Good,” she said. “I like her.”

“She isn’t you.”

“And you wouldn’t want her to be,” Madeline said, slowly shaking her head. “What we had belongs to us.”

Dark Exodus

Dark Exodus A Hundred Words for Hate rc-4

A Hundred Words for Hate rc-4 The Fallen

The Fallen Where Angels Fear to Tread rc-3

Where Angels Fear to Tread rc-3 Armageddon

Armageddon The Satan Factory

The Satan Factory In the House of the Wicked: A Remy Chandler Novel

In the House of the Wicked: A Remy Chandler Novel A Hundred Words for Hate

A Hundred Words for Hate Sleeper Code

Sleeper Code The Demonists

The Demonists Specter Rising (Brimstone Network Trilogy)

Specter Rising (Brimstone Network Trilogy) Dancing on the Head of a Pin

Dancing on the Head of a Pin The Shroud of A'Ranka (Brimstone Network Trilogy)

The Shroud of A'Ranka (Brimstone Network Trilogy) The Flock of Fury

The Flock of Fury Where Angels Fear to Tread

Where Angels Fear to Tread Leviathan

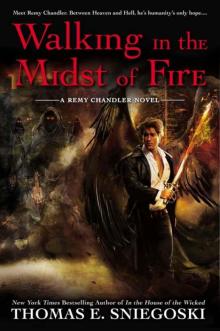

Leviathan Walking In the Midst of Fire: A Remy Chandler Novel

Walking In the Midst of Fire: A Remy Chandler Novel Billy Hooten

Billy Hooten Monstrous

Monstrous Lobster Johnson: The Satan Factory

Lobster Johnson: The Satan Factory Legacy

Legacy Savage

Savage Walking In the Midst of Fire rc-6

Walking In the Midst of Fire rc-6 The Fallen 4

The Fallen 4 A Deafening Silence In Heaven

A Deafening Silence In Heaven A Kiss Before the Apocalypse

A Kiss Before the Apocalypse The God Machine

The God Machine Sleeper Agenda

Sleeper Agenda The Girl with the Destructo Touch

The Girl with the Destructo Touch Dancing On the Head of a Pin rc-2

Dancing On the Head of a Pin rc-2 In the House of the Wicked rc-5

In the House of the Wicked rc-5 Reckoning f-4

Reckoning f-4 The Fallen 3

The Fallen 3 The Brimstone Network (Brimstone Network Trilogy)

The Brimstone Network (Brimstone Network Trilogy) The Fallen 2

The Fallen 2 The Fallen f-1

The Fallen f-1