- Home

- Thomas E. Sniegoski

A Hundred Words for Hate rc-4 Page 4

A Hundred Words for Hate rc-4 Read online

Page 4

“And only us,” Remy added.

“Exactly.” She leaned forward in her chair, her lips suddenly so close to his.

“No more wasted guilt,” she whispered, as their lips touched.

Remy opened his eyes to the reality of his world.

The Maine cottage was gone, as was his wife. Instead he sat at his desk, where he had been finishing some billing when he’d closed his eyes and let his consciousness wander. An angel needed no sleep, but often he would enter a kind of fugue state to rest his weary mind and spend time with his wife.

Marlowe lay flat on his side on the rug beneath the desk, legs outstretched as if he’d been shot, his dark eyes watching Remy.

The clock at the bottom of the computer screen said that it was after three a.m., and the street outside his Beacon Hill brownstone was quiet. Maybe it was time to alleviate some more of his burdened conscience.

“Hey,” Remy said to his dog.

Marlowe sat up at full attention, head tilted, waiting for Remy to ask the question.

And he did. “Want to go to the Common for a walk?”

No more magickal words had ever been spoken.

The Labrador immediately sprang to his feet and began to anxiously pace.

“Guess that’s a yes.” Remy stood and stretched, then headed for the stairs, a very excited Marlowe at his heels.

As Remy was getting ready to take Marlowe on a nighttime walk, Fernita Green was dreaming.

She had fallen asleep in her living room chair, as she was wont to do these days, surrounded by the clutter of her life, Miles the cat curled tightly in her lap, also deeply asleep.

Sharing the dream of his mistress.

Fernita walked through the jungle, tall grasses and thick underbrush moving aside to allow her to pass.

Leading her.

Miles purred and chirped, enjoying the freedom of this place that could only be the world found on the other side of the window.

The big outside.

Something deep inside told Fernita that she knew this vast, primordial place, and this calmed her as she walked the path that appeared beneath her bare feet.

Where are my shoes? she wondered briefly, for there were far more important things to worry about. Although she could not remember what they were.

Only that she was the answer.

The jungle path abruptly stopped, a curtain of thorny vines blocking her way. Fernita stood before the obstruction, waiting for the vegetation to show her the way around, but the green did not react, softly rustling in the warm, gentle breeze that caressed this wild place.

The wild was awakened in Miles the cat, his large eyes scanning the grass and trees for signs of birds, or bugs, or squirrels—signs of prey.

But, disappointingly, there were none right then. There were only the plants here in the big outside.

The jungle closed in around her. Fernita watched with a growing sense of unease as the path she’d walked slowly filled in behind her, reclaimed by the abundant overgrowth. A twinge of panic struck, but she managed to keep it under control as she turned her attention to the wall of thick, spotted vines dangling before her.

She did not know why, but she was suddenly overcome with the desire to touch them. Before she could even question this nearly overpowering compulsion she reached out, then quickly withdrew her hand with a hiss as a thorn pierced the underside of two of her fingers and her palm. For a moment she stared at the dark blood pooling in her hand, then returned her attention to the thick vine before her.

At first she believed it to be a trick of her eyes. There was blood on the vines where she had touched them . . . where she had been stuck, but the blood seemed to be fading away, gradually absorbed into the body of the vines.

How odd.

And as the last of her blood was taken in, the vines began to sway and shake, slowly pulling up and away like the thick velvet curtains of the old movie palaces, to reveal not the white of a screen, but a dark, winding path beyond.

Fernita crouched at the opening, Miles cowering beside her, neither sure they wanted to go any farther, even though every fiber of Fernita’s being screamed that she should.

The high grass had again receded, forming a snaking passage through the abundant jungle to a clearing. And in the clearing was a tree; perhaps one of the largest trees Fernita had ever seen. She could just about make out the vast network of thick branches that grew out from its massive trunk, tapering upward into the velvet black sky.

How odd the stars appeared, almost as if they were too close.

Fernita’s eyes were just returning to the path . . . to the glorious tree, when something stepped out of the shadows to block her view.

It was huge, its body covered in golden armor that reflected the brightness of the burning sword it clutched in one of its massive, gauntleted hands.

Frozen in fear, she could only look up into its face, which was equal parts eagle, lion, and man.

What are you? she wanted to ask it, but the answer was upon her, floating up from the darkness from where it had been hidden.

Cherubim.

“You do not belong,” the creature shrieked, roared, and bellowed in one discordant voice that made her bones shake.

And Miles hissed, his body pressed flat to the grassy ground, fur standing on end as if electrified.

It pinned her there with its multiple sets of eyes, its large form casting a cold shadow across her naked form.

It was the first moment that she recognized she was unclothed, and it would have caused her much confusion if she hadn’t been in the presence of a looming weapon of Heaven.

The Cherubim lumbered ever closer; four sets of strangely beautiful wings unfurled from its armored back. Though terrified, she could not help but marvel at its fearsome beauty, staring up into its three faces as it lifted its sword of fire.

“You do not belong,” it announced again, prepared to strike.

And Fernita watched, unable to move as the fiery weapon descended, her mouth opening, not in a scream as she believed would pour forth from the depths of her very soul, but another sound that proved she was the answer.

That she did belong.

Fernita awakened from the dream, the answer to a question that had plagued her for so very long dancing upon the tip of her tongue.

For a moment it was there, but as the recollection of the jungle drifted away like the morning mist, it too was gone. And in a matter of seconds, she had forgotten that she had even dreamed at all.

Miles had moved from her lap to an open portion of windowsill, staring intensely out at the cold, predawn world, a strange trilling sound, as if he were excited by the sight of a bird or a squirrel, coming from his furry throat.

“What do you see out there, crazy cat?” she asked sleepily, as she reached out and stroked his back with old fingers, crooked with age.

Miles continued to stare, repeating the strange sound over and over again, answering the question that the old woman asked of him.

“It’s coming,” the cat told her, even though she did not understand.

“The big outside is coming.”

CHAPTER THREE

“Watch out for the rats,” Remy called out to Marlowe as he stuffed the dog’s leash in his back pocket and sat on a bench in Boston Common.

“Rats?” Marlowe questioned, stopping beside an old oak tree. He looked around, his nose twitching in the cold early-morning air.

“I didn’t say there were any waiting to attack you; just be careful. You don’t want to get bitten and have to go to the vet for shots.”

“No shots,” Marlowe growled, nose to the frozen ground. “No rats . . . no bite . . . no shots,” the Labrador grumbled, a checklist to make this visit next to perfect.

Remy chuckled. It was still relatively dark in the Common, and he and Marlowe seemed the only living things willing to brave the more than chilly early morning. Still, he wanted to keep an eye on the dog; sometimes Marlowe’s enthusiasm got away from him.<

br />

“And don’t eat any garbage!” Remy called out as an afterthought, one more thing for the checklist. The dog didn’t respond, but Remy was sure he’d heard.

Remy settled in on a bench, crossing his legs and resting his arm atop the back, looking as though he were relaxing on a mild summer’s night. It was so cold that even the homeless who often frequented the Common appeared to have sought more protective shelter elsewhere.

Good for them, Remy thought. This was the kind of weather that could kill if you weren’t careful.

Looking around at his surroundings, Remy realized that it had been some time since he and Marlowe had been here, long enough for the city to put in some new, freshly painted trash barrels to replace the old rusted and dented ones. He considered pointing them out to his dog, who was pawing at a patch of frozen grass, but decided it would be better not to offer an opportunity for food. Marlowe’s appetite was voracious, occasionally getting the better of him, and Remy preferred not to deal with the consequences.

A spot of rich green amid the skeletal branches of a nearby tree caught Remy’s attention, and he found himself staring. It was odd to find such vibrant leaves in the dead of winter—and even odder to find so many.

And then he noticed that the explosion of plant life seemed to be all around him, in the trees, in the bushes, and even in thick patches of grass that seemed to have erupted up through the old snow and ice.

A sudden barrage of barks distracted him from the oddity of nature, and Remy quickly stood to find his dog.

The sun was just about ready to rise, and he could see Marlowe had something pinned against one of the new trash barrels. He was darting from side to side, barking and growling.

“Marlowe, no,” Remy commanded, knowing exactly what he’d find as he headed for the ruckus.

The rat was huge, fat, and it glared at the dog, its beady eyes glistening red in the first light of morning, bristling, brown-furred back pressed against the barrel.

“Rat,” the dog barked angrily. “Rat take bread.”

“What bread?” Remy asked as he approached, careful not to slip on the packed snow as he left the relative safety of the paved walkway.

“My bread,” Marlowe barked again, lunging at the now hissing rat.

“You don’t have any bread,” Remy reminded the frenzied animal. And then he saw it. The overweight rodent had taken possession of the end of a submarine sandwich roll . . . a roll to which a certain Labrador retriever, even though he’d been warned not to eat any garbage, had taken a particular shine.

“No,” Remy ordered, reaching over to grab his dog’s collar. “It’s not your bread. . . . It’s garbage, and what did I tell you about garbage?”

“Not garbage.” Marlowe’s eyes were riveted to the roll. “Bread.”

“If you found it on the ground, it’s garbage.” He tugged on the collar as Marlowe tried to pull away.

Remy looked at the rat and spoke in its primitive tongue. “We’re sorry,” he said. “Take your prize and go.”

The rat glared at him, its damp nose twitching in the air, testing for danger. It did not trust him.

Remy pulled Marlowe away.

“No!” the dog protested with a pathetic yelp.

“No?” Remy repeated. “How about yes?”

The rat’s bulk loomed over the piece of roll as it eyed them cautiously. “Mine,” it squeaked. “Hate dog. Hate man,” it added with a dismissive hiss, as it snatched up the bread and scampered off.

“And furthermore, what did I tell you about rats?” Remy asked the dog, releasing the hold on his collar.

“Filthy,” Marlowe said, already sniffing at the ground and ready to move on.

“Yeah, filthy,” Remy said. He glanced at his watch and saw that it was nearing five thirty. “Want to go home and get some breakfast?”

That caught the dog’s attention.

“Eat?” Marlowe asked.

“Would I lie to you?” Remy questioned, smiling, the love that he felt for this simple animal nearly overwhelming.

“No lie,” the Labrador said, excitement in his doggy voice. “Eat. Eat now.”

“Well, c’mon, then.” Remy gestured for Marlowe to follow him.

As he turned, he caught sight of three figures on the path up ahead of him, and took Marlowe’s leash from his pocket. “Come here.” He reached down to clip the leash to the dog’s collar. “Just in case you get any ideas about bothering these early risers.”

“No bother,” Marlowe said, but his tail was already wagging furiously. Marlowe loved people, but could never understand that some people didn’t love dogs, especially big ones that seemed overly excited.

“Behave yourself,” Remy told him, pulling up on the leash as they grew closer to the three figures.

He saw that they were eyeing him and he made it a point to pull Marlowe even closer.

“Good morning,” Remy said to the first of the men, a short, dark-haired, dark-skinned fellow, probably in his mid-twenties, bundled up in a heavy woolen cap and puffy jacket. The other two men were similarly dressed.

The three stopped and watched Remy as he passed, Marlowe struggling, desperate to say hello.

“Don’t worry about him,” Remy explained with a smile. “He just gets excited around people. Doesn’t have an aggressive bone in his body.”

He tugged at the dog’s leash, continuing toward the exit when he heard one of them speak.

“Remy Chandler?”

He stopped and turned.

“Yes?”

“You are Remy Chandler . . . the private investigator?” the shortest of the three men said.

“I am,” Remy answered. “And you are?”

“My name is Jon,” the man said, pulling off one of his gloves as he stepped toward Remy, offering his hand. “We’ve been looking for you.”

Remy shook the man’s hand as the other two nodded. The handshake was warm and firm.

“Really,” he said. The man had an odd speech pattern, as if he was quite hard of hearing.

Marlowe pulled forward on the leash, barking for some attention.

“Knock it off,” Remy said, giving the leash a tug.

“That’s all right,” the man said, squatting down to vigorously pet the dog behind the ears. “He seems like a good dog.”

“Very good,” Marlowe grumbled, finally getting the attention he so desperately craved.

“He tries,” Remy said, giving Marlowe’s butt a swat. “So, you say you’ve been looking for me?” There was a strange vibe coming off the men, but one he couldn’t quite read. The only thing that he could tell—could feel—was that they weren’t dangerous, and meant him no harm.

“We have,” Jon said, his breath coming in roiling clouds of white as he slid his hand back into his glove. “We were told you were here, but we didn’t know where exactly. It’s so cold we were about to give up.”

The others smiled as they nodded again, obviously pleased they had managed to stick it out.

“That’s funny,” Remy said. “I don’t remember telling anybody that I’d be here.”

“You didn’t have to,” Jon said. “We listen to our surroundings, and in turn, they tell us what we need to know.”

Okay, not dangerous, but very likely crazy.

“So your surroundings said I’d be at the Common, walking my dog?”

Jon bent at the waist in a stiff bow. “They did indeed. I believe it was an elm. . . .”

“Maple,” one of the others corrected.

“Ah, yes, thank you. A maple tree on Pinckney Street told us that you had passed with your friend here.”

Remy smiled carefully. “A tree told you I went to the Common?”

“It mentioned you had passed, as did the others you walked by on your way here.”

“More than one tree talked to you?” Remy asked incredulously.

“All plant life upon this planet talks to us,” Jon said with a beatific smile. “You probably think we’re mad,” he add

ed.

Remy laughed. “Well, since you brought it up.”

“We are the Sons of Adam,” Jon said, pointing to his comrades, and then to himself.

It took a moment for their identities to sink in.

“Sons of Adam,” Remy repeated slowly as the meaning of the words began to permeate his thick skull. “The Adam?”

“Exactly,” Jon said. “And he’s sent us here to find you.”

Marlowe, tired of all the talking, flopped down onto the cold path, lifted his leg, and began to lick at his lower regions.

A real class act.

Remy was silent, anticipating what was coming next.

“The first father has need of your special skills,” Jon continued.

“Adam needs you to find something for him. He asks that you find the key . . .

“. . . the key to the Gates of Eden.”

Hell

Francis really didn’t know what to expect when he died, but it wasn’t this.

Every inch of his body ached. Even thinking hurt, and although he tried to throw himself into a pool of sweet, sweet oblivion, it just wasn’t meant to be.

He’d always said thinking could be bad for you, but this was the first time he had actual physical proof.

Tiny hand-grenade blasts were going off inside his skull, all over the surface of his brain, and they forced him to scream like a little girl.

A tough little girl with a penchant for medieval weaponry, and a dry wit.

Francis cautiously opened his eyes. His brain was on fire, as was his skin. Even his eyelids felt as if they’d been ripped from his skull, and put back with random staples.

He rolled over on what appeared to be the floor of a cave, the sounds of Hell still reshaping themselves in the distance. As his eyes adjusted to the gloom of his surroundings, he forced himself to look around.

A flash of memory—like a hot poker being shoved into his ear—jumped into his thoughts, but was quickly gone in a flesh-rending screech of spiked tires.

Gone, but what he had seen was not forgotten.

He remembered lying on the ground, ready to die . . . ready to be swallowed up by one of the many molten pools opening up on the blighted surface of Hell. And just as he was about to give in to the fury being unleashed, he saw the figure of a man.

Dark Exodus

Dark Exodus A Hundred Words for Hate rc-4

A Hundred Words for Hate rc-4 The Fallen

The Fallen Where Angels Fear to Tread rc-3

Where Angels Fear to Tread rc-3 Armageddon

Armageddon The Satan Factory

The Satan Factory In the House of the Wicked: A Remy Chandler Novel

In the House of the Wicked: A Remy Chandler Novel A Hundred Words for Hate

A Hundred Words for Hate Sleeper Code

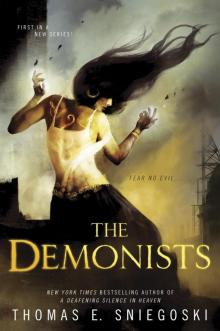

Sleeper Code The Demonists

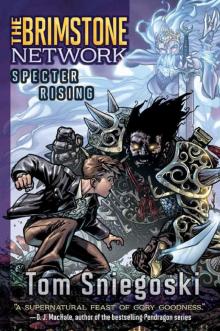

The Demonists Specter Rising (Brimstone Network Trilogy)

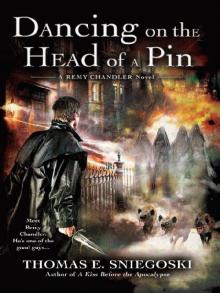

Specter Rising (Brimstone Network Trilogy) Dancing on the Head of a Pin

Dancing on the Head of a Pin The Shroud of A'Ranka (Brimstone Network Trilogy)

The Shroud of A'Ranka (Brimstone Network Trilogy) The Flock of Fury

The Flock of Fury Where Angels Fear to Tread

Where Angels Fear to Tread Leviathan

Leviathan Walking In the Midst of Fire: A Remy Chandler Novel

Walking In the Midst of Fire: A Remy Chandler Novel Billy Hooten

Billy Hooten Monstrous

Monstrous Lobster Johnson: The Satan Factory

Lobster Johnson: The Satan Factory Legacy

Legacy Savage

Savage Walking In the Midst of Fire rc-6

Walking In the Midst of Fire rc-6 The Fallen 4

The Fallen 4 A Deafening Silence In Heaven

A Deafening Silence In Heaven A Kiss Before the Apocalypse

A Kiss Before the Apocalypse The God Machine

The God Machine Sleeper Agenda

Sleeper Agenda The Girl with the Destructo Touch

The Girl with the Destructo Touch Dancing On the Head of a Pin rc-2

Dancing On the Head of a Pin rc-2 In the House of the Wicked rc-5

In the House of the Wicked rc-5 Reckoning f-4

Reckoning f-4 The Fallen 3

The Fallen 3 The Brimstone Network (Brimstone Network Trilogy)

The Brimstone Network (Brimstone Network Trilogy) The Fallen 2

The Fallen 2 The Fallen f-1

The Fallen f-1